Fracture Blisters: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment Options

Imagine you’re in the emergency room, your ankle throbbing after a bad fall. The doctor confirms it: you’ve broken a bone. But then, a few days later, you notice something strange—blisters forming on your skin, right over the fracture site. You’re confused, maybe even a little worried. What are these blisters, and why are they there?

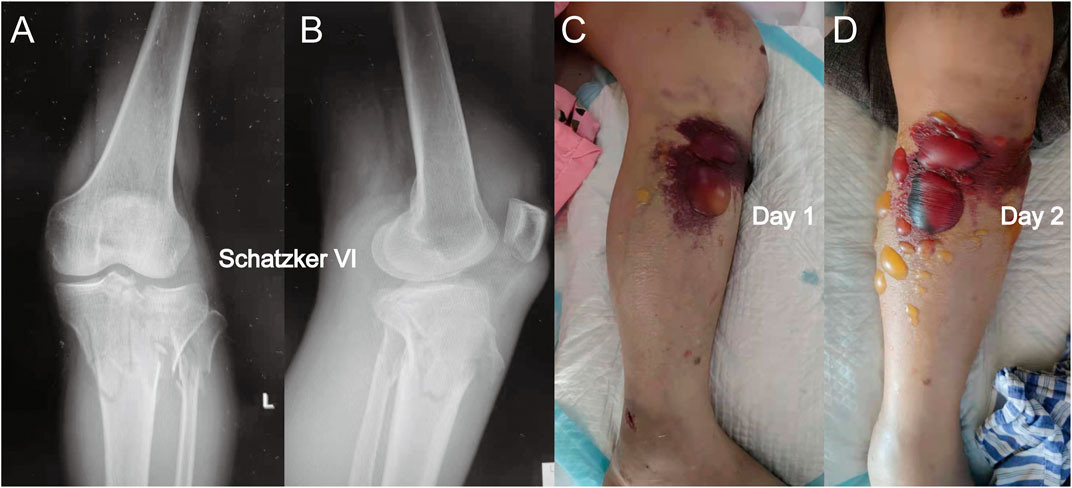

(A Proximal Leg Fracture with Fracture Blister developed over it)

What Are Fracture Blisters?

Fracture blisters are fluid-filled vesicles or bullae that

form on the skin overlying a fractured bone. They are a sign of significant

soft-tissue injury and occur in approximately 2.9% of all fractures requiring

hospitalization (Verywell Health). These blisters are most commonly seen in

areas where the skin adheres tightly to the bone with little subcutaneous fat,

such as the ankle, wrist, elbow, foot, and distal tibia. They resemble

second-degree burns in appearance but are caused by mechanical trauma rather

than heat.

Fracture blisters can be single or multiple and may appear

directly over the fracture or at a distance, depending on the injury’s impact

on surrounding tissues. They are more likely to occur in high-energy injuries,

such as motor vehicle accidents or falls from significant heights, but can also

develop in low-energy trauma, like a moderate ankle sprain, in up to 25% of

cases.

Pathophysiology: How Do Fracture Blisters Form?

The exact cause of fracture blisters remains partially

elusive, but research suggests that damage to the dermal-epidermal junction—the

interface between the skin’s outer (epidermis) and inner (dermis) layers—plays

a central role. When a bone fractures, particularly with significant force, the

skin experiences shearing stresses that can separate these layers, creating a

potential space for fluid accumulation.

A 1995 biomechanical study by Giordano et al. demonstrated

that the tension induced by fracture deformation causes this dermal-epidermal

separation in cadaveric ankle skin specimens. The study highlighted that the

differing elasticity and viscoelastic properties of the dermis and epidermis

lead to layer splitting when critical strain is reached. Post-traumatic edema

(swelling) increases interstitial pressure, reducing cohesion between epidermal

cells and promoting fluid transfer into the blister cavity (PMC Article).

Additionally, damage to local blood vessels and lymphatics

contributes to venous stasis and tissue hypoxia, which can lead to epidermal

necrosis. This combination of mechanical stress, swelling, and reduced oxygen

supply creates the perfect storm for blister formation. Histologically, a 1993

study by Varela et al. confirmed a typical dermo-epidermal junction split with

re-epithelialization, noting that intact blisters are sterile but become

colonized with pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus

epidermidis upon rupture.

Types of Fracture Blisters

Fracture blisters are classified into two clinical and

histological types:

|

Type |

Location of Cleavage |

Characteristics |

Healing Time |

Complications |

|

Clear Fluid-Filled (Subcorneal) |

Within the epidermis, above the granular layer |

Contains clear, gel-like serum; minimal dermal damage;

heals without scarring |

~13 days |

Lower risk |

|

Blood-Filled (Subepidermal) |

Between epidermis and dermis |

Contains blood from damaged papillary dermal vasculature;

may scar or alter pigmentation |

~16 days |

Higher risk |

Both types indicate a cleavage injury at the

dermal-epidermal interface, but blood-filled blisters are associated with more

severe tissue disruption, increasing the likelihood of complications like

infection or wound dehiscence.

Where and When Do Fracture Blisters Occur?

Fracture blisters are most frequently observed over

fractures of the ankle and proximal tibia, followed by the wrist, elbow, and

foot. These areas are prone due to their thin skin, minimal subcutaneous fat,

and lack of cushioning muscle or tissue. For example, the ankle has few hair

follicles, sweat glands, or deep veins, making the skin particularly vulnerable

(DermNet NZ).

Timing is variable:

- Typical

Onset: 24–48 hours post-injury, with an average of 2.5 days.

- Range:

As early as 6 hours or as late as three weeks.

- Post-Surgical:

Can occur after elective foot and ankle surgery.

Blisters may not always form directly over the fracture

site; they can appear at a distance due to the injury’s broader impact on soft

tissues. Curiously, areas like the wrist, elbow, and foot, despite having

similar skin characteristics, are less commonly affected, possibly due to

differences in injury patterns or tissue dynamics.

Risk Factors

Fracture blisters are more likely in:

- High-Energy

Injuries: Falls from heights (~18 feet), motor vehicle accidents, or

Gustilo Anderson Grade I/II open tibia fractures.

- Low-Energy

Trauma: Up to 25% of cases, such as ankle sprains or moderate blunt

trauma.

- Predisposing

Conditions: Diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, collagen

vascular disease, hypertension, smoking, alcoholism, and lymphatic

obstruction, all of which impair wound healing.

Notably, age, sex, race, overall health status, concurrent

injuries, or initial fracture treatment do not appear to influence blister

formation.

Diagnosing Fracture Blisters

Diagnosis is primarily clinical, based on the appearance of

tense, fluid-filled vesicles or bullae on swollen skin overlying a fracture.

Healthcare providers should document:

- Number

of blisters

- Location

- Size

- Type

(clear or blood-filled)

No specific diagnostic tests are required, though imaging

(e.g., X-rays, CT scans) is used to assess the underlying fracture. The

blisters are generally painless, similar to friction blisters or second-degree

burns, but their presence can be daunting for patients and inexperienced

clinicians.

Managing Fracture Blisters

The management of fracture blisters is a complex and

controversial topic, with no universal consensus in the medical literature. The

primary challenge is balancing the need for timely fracture stabilization with

the protection of compromised skin to minimize complications.

General Principles

- Intact

Blisters:

- Should

be left undisturbed, as the blister roof serves as a sterile biological

dressing, reducing infection risk (Healthline).

- Gentle,

non-adherent dressings (e.g., Aquacel, gauze) can be applied to protect

the area.

- Ruptured

Blisters:

- Require

cleaning and dressing with moist, non-occlusive dressings to promote

healing.

- Topical

agents like silver sulfadiazine (Silvadene) are commonly used to prevent

infection and aid re-epithelialization, particularly in non-diabetic

patients (PubMed Study).

- Silver-coated

dressings may reduce pain and shorten healing time.

Surgical Considerations

- Delaying

Surgery:

- Most

experts recommend delaying surgical fixation until blisters resolve,

typically 7–10 days, to reduce the risk of wound complications (PMC Article).

- Average

delays vary by fracture type:

|

Fracture Type |

Average Delay (Days) |

|

Ankle | 6 |

|

Tibial Plateau |

11 |

|

Tibial Shaft |

3.5 |

|

Calcaneal |

12 |

|

Pilon |

6.75 |

|

Mean |

7.7 |

- Early

Surgery:

- In

high-energy trauma, surgery within 24–48 hours may stabilize the fracture

and reduce further soft-tissue damage, potentially preventing blister

formation.

- Incisions

should avoid blister beds, as crossing them can double the risk of

infection and wound dehiscence.

- Alternative

Approaches:

- If

surgery is urgent, incisions can be made through the blister bed (less

preferred) or planned to avoid blisters entirely.

- The

AO Foundation recommends waiting 7–10 days for non-urgent surgeries if

blisters are present.

Advanced Techniques

- Negative

Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT):

- Also

known as a “wound vac,” NPWT may accelerate blister healing, allowing

earlier surgical intervention (Verywell Health).

- Blister

Aspiration or Deroofing:

- Some

studies support aspirating or deroofing blisters and treating the bed

with antimicrobials, but this should be done cautiously due to infection

risks (EFORT Open Reviews).

- A

2025 systematic review found evidence supporting this approach in

controlled settings.

Patient-Specific Factors

Patients with comorbidities like diabetes or vascular

disease require close monitoring and may need hospital admission if blisters

develop. Early recognition and tailored wound care are critical in these

high-risk groups.

Potential Complications

Fracture blisters can significantly complicate fracture

management:

- Infection:

Ruptured blisters or incisions through blister beds increase the risk of

bacterial colonization and surgical site infections.

- Wound

Dehiscence: Surgical wounds may fail to heal properly, leading to

prolonged recovery.

- Delayed

Healing: Both the fracture and skin may take longer to heal, extending

hospital stays.

- Chronic

Ulcers: Rare but possible in severe cases.

- Scarring

and Pigmentation Changes: More common with blood-filled blisters due

to deeper tissue damage.

A study by Strauss et al. reported a 13% prevalence of wound

complications in 45 patients with lower extremity fracture blisters.

Blood-filled blisters are particularly concerning, with six out of seven skin

complications in one study requiring split-thickness skin grafting.

Preventing Fracture Blisters

While not always preventable, early surgical stabilization

within 24 hours of injury may reduce blister formation by minimizing ongoing

soft-tissue trauma. This is particularly relevant for high-energy injuries.

Additionally, careful monitoring of high-risk patients and prompt wound care

can mitigate complications.

Fracture blisters are a fascinating yet challenging aspect

of orthopedic trauma. They highlight the intricate relationship between bone

and soft tissue in the healing process. For patients, understanding fracture

blisters can demystify a potentially alarming complication, while for

healthcare providers, it underscores the need for careful, individualized

management. By respecting the blisters’ role as a natural barrier, avoiding

unnecessary interventions, and prioritizing wound care, we can optimize outcomes

for patients with fractures.

Whether you’re a patient navigating recovery or a clinician

managing complex cases, fracture blisters remind us that even the smallest

details—like a blister on the skin—can have a big impact on healing.

Comments

Post a Comment